Wu Guanzhong

-Prestige-Art-Gallery-品艺画廊.jpg)

Wu Guanzhong Two Swallows 1998 Ink and Colour on Paper (sold for RMB 46 million in 2011, Beijing Poly International Auction)

Wu Guanzhong

(August 29, 1919 – June 25, 2010)

Details:

1919

Born in Yixing, Jiangsu Province, China

1942

Graduated from the National Academy of Art, China

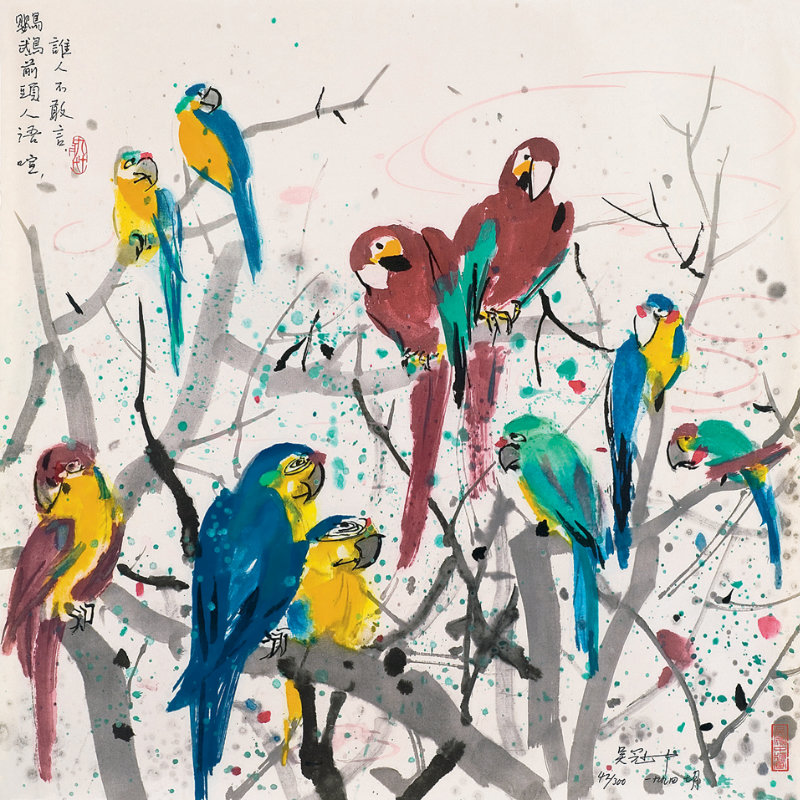

Wu’s innovative approach, known as “color ink painting,” earned him acclaim as one of trio, alongside Zhu Dequn and Zao Wou-Ki that redefines the 20th-century modern art scene, not just in the East, but worldwide.

Wu Guanzhong

Wu Guanzhong (August 29, 1919 – June 25, 2010), also known as Tu, was a Chinese painter and art educator born in Yixing, Jiangsu Province, China. He was a pioneering figure in modern Chinese painting, blending Western and Eastern influences to create unique artworks. Graduating from the National Academy of Art, Wu studied under renowned artists Fang Ganmin and Pan Tianshou, exploring both oil painting and Chinese ink techniques.

Throughout his career, Wu focused on the nationalisation of oil painting and the modernisation of Chinese painting. His innovative approach, known as “colour ink painting,” earned him acclaim as one of the trio, alongside Zhu Dequn and Zao Wou-Ki, that redefined the 20th-century modern art scene, not just in the East, but worldwide. Often hailed as the “Three Musketeers” of Chinese Modern Art, the three highly esteemed artists were pioneers of their generation, integrating traditional Chinese painting techniques into Western abstractionism.

Unique Creative Techniques

Wu Guanzhong had his own perspective on traditional Chinese art. He expressed scepticism about the techniques and formulas of traditional Chinese ink painting, such as various types of brush strokes, and the integration of poetry, calligraphy, and painting in contemporary creation. In his view, these formulas led to weakened creativity and rigid expression. He believed that repeatedly using these formulas to create standardised symbolic patterns was akin to “repeating old stories with outdated language.” Wu advocated that modern literati painting must absorb the nutrients of Western art, expanding from a single literary-oriented mindset to modern modelling spaces like sculpture and architecture. He also viewed the notion of “absorbing foreign influences on the basis of tradition” as merely one perspective, believing that the changes of the times nurture new forms of painting. Artists can freely decide the importance of traditional elements and foreign influences. Wu chose to use “modern Chinese and foreign languages” to make “the unique temperament of the Chinese nation known to the world.”

Donations

In 1999, Wu Guanzhong donated ten works to the National Art Museum of China. In 2008, he donated his masterpiece “1974·Yangtze River” to the Palace Museum. The Shanghai Art Museum, the Zhejiang Provincial Government, and his alma mater, the China Academy of Art, have also received numerous donations from him. That same year, Wu donated 113 works to the National Gallery Singapore.

Auctions

On April 4, 2016, Wu Guanzhong’s oil painting “Zhouzhuang” was sold at Poly Auction Hong Kong 2016 Spring Auction’s “Chinese and Asian Modern and Contemporary Art” session for HKD 236 million, setting a new auction record for Wu’s work and breaking the auction record for Chinese modern and contemporary oil paintings.

In the Eyes of Masters

In a memoir essay, Chen Danqing described Wu Guanzhong as follows: “Later, as I gradually saw past materials and images, I realised that Mr. Wu’s public speaking style retained the fervour of a leftist youth from the Republic of China era, passionate and assertive, as if mobilising for the national crisis during the war of resistance. During an early 21st-century visit, when he was over eighty, his demeanour remained upright and assertive, confident in every word, almost argumentative. His face was originally gaunt and resolute, and when he spoke with pleasure, it was always with a decisive air, as if he were angry.”

Mo Yan once said, “Mr. Wu Guanzhong said he admired three people the most in his life: Lu Xun, Van Gogh, and his wife. Lu Xun provided him with thoughts, Van Gogh with revolutionary art, and his wife ensured his logistics. He said, ‘A hundred Qi Baishi’s are not worth one Lu Xun,’ which is actually an extreme statement by an artist to emphasise the importance of thought for artists. Artists with personality often make many definitive statements; don’t nitpick their words. He was expressing a strong emotion, hence the absolute language. If Mr. Wu hadn’t said it this way, would people remember? For example, if he had said, ‘Painters should also read literature! Literature is very important!’ people would have forgotten. But when he said, ‘A hundred Qi Baishi’s are not worth one Lu Xun,’ everyone remembered. He also said, ‘Brush and ink equal zero,’ to emphasise a point. He knew brush and ink don’t equal zero. It’s an extreme statement not meant to be taken literally, because great art is also incomparable.”

Early Spring in the Purple Bamboo Garden

1973

Oil on Canvas

60cm x 81cm

Former Residence of Qiu Jin

2002

Oil on Canvas

70cm x 140cm

Sold for ¥74.75 million in 2011, Beijing Poly international Auction

-Prestige-Art-Gallery-品艺画廊.jpg)

The Lion Grove Garden

1988

Ink and Colour on Paper

173cm x 290cm

-Prestige-Art-Gallery-品艺画廊.jpg)

Exhibitions

Past

Wu Guanzhong and Chua Soo Bin

13 Apr - 18 Jun 2024

10am - 6pm

Singapore